SOURCES: Industrial Archeology of Columbus, Georgia: A Tour Guide for the 8th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial Archeology, April 1979 by Dr. John S. Lupold, Columbus, Georgia 1828 - 1978 by Dr. John S. Lupold, the Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress, Investigations into the Historic Mill Dams of the Chattahoochee River by Southern Research, and The West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail by Center for Public History at the University of West Georgia, 2015.

In the fall of 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau became active in administering the land program in Georgia and returned much African American labor to the fields, mediating a contract-labor system between white landowners and their Black workers, many of whom they formerly enslaved. Field work—once the province of entire Black families—was transformed as the freedwomen withdrew their labor and their children’s labor to the household. Both children and adults began to take advantage of educational opportunities, usually offered by teachers from the North. Often education was associated with the burgeoning number of all-Black churches that also characterized Reconstruction. Some of the former enslaved individuals and families were flocking to towns, where they encountered overcrowding and a shortage of food. A large number of Black Georgians fell prey to epidemic diseases. Meanwhile, on farms and plantations that had depended on enslaved labor, harvests were small, with poor planning and miserable weather further diminishing them. Corn and wheat were scarce in late 1865. The state’s traditional money crop, cotton, plummeted following the Civil War to around 50,000 bales from a high in 1860 of more than 700,000 bales. From the 1870s to the 1950s, thousands of rural African Americans migrated to Columbus to build a better life. A commercial revival alone would fail to employ the hundreds of idle workers – white and newly freed – following the Civil War in Columbus. The town still desperately needed a revival of its many industries. The iron foundries recovered first. Men who had learned iron working during the war continued in the business. The rebuilt foundries began operating with a month after Wilson’s raid. In 1860, the city had only two foundries; by 1870, it had eight. (One still in operation today – Goldens’ Foundry (1882) – will be featured in Part III.)

The Columbus Iron Works, the largest iron producer, manufactured a full range of small cast iron items, like the small foundries, but their most important products came from the expertise gained during the war. They made a large variety of steam engines and even steamboats. After several unsuccessful attempts, it helped to manufacture an ice machine in 1872. By the 1880s, the company guided by H.D. Stratton perfected a cheap, uncomplicated, safe ice machine. The Iron Works manufactured these machines in large numbers and sold them to ice houses, dairies, and hospitals, thus becoming the first company to successfully market a commercial ice machine which was distributed throughout the nation and Latin America for the next forty years.

Other Columbus manufacturers rapidly began after the war. By the early 1870s, Columbus factories and shops manufactured rope, jute bagging, cottonseed oil, carriages, furniture, and cigars. Bricks and lager beer were produced across the river in Girard. Unique for a medium-sized southern city was the extensive chemical laboratory of J.S. Pemberton. He employed chemists and pharmacists who distilled a whole range of pharmaceuticals, patent medicines, hair restorers, perfumes, paints, photographic chemicals, and a great variety of sparkling soda water (such as French Wine of Coca which evolved into Coca-Cola when he moved to Atlanta in 1880) which he dispensed in his drugstore. Columbus’ chief industry was, of course, the textile mills – which had all been burned by Wilson. Clapp’s Factory resumed first, as early as December 1865. In 1867 and 1868, two of Columbus’ most significant textile mills would be formed – The Eagle & Phenix and Muscogee Manufacturing Company. During the 1870s, textile manufacturing expanded more rapidly in Columbus than in any other southern city, even though only two companies occupied the Columbus riverfront sites. Muscogee Manufacturing Company (1867) utilized one lot, while the Eagle and Phenix (1866) --the South's largest mill in the late l870s--eventually controlled the other eighteen lots.

Muscogee Manufacturing Company began on water lot #1, the site of Coweta Falls Factory {1844), the city's first textile mill. In 1868, George Parker Swift, a New Englander who established mills in Upson County, Georgia, before the Civil War, began constructing Muscogee No. 1. In 1880, he built an almost rectangular Mill No. 2 to fill the remaining space on this water lot. (These two structures were demolished in 1978.) Future expansion occurred north of 14th Street, where the company lacked riparian rights. Steam-powered Mill No. 3 (1887), and electricity from the Columbus Railroad Company powerhouse at City Mills drove No. 4 (1904). Later additions included Mill No. 5 (1918), No. 6 (1928), and No. 7 (1950). In the process, the complex incorporated the Mott House (a three-story 1840s mansion) as offices and the city's 1907 Carnegie Library as a machine shop. Fieldcrest purchased this company from its local owners in 1963. In 1997, plans for the international headquarters of TSYS were developed for the Muscogee Mills site. TSYS worked diligently with local, state, and federal preservation groups to develop a plan respecting the history of the area. The new campus would incorporate a stabilized Mott House (later destroyed by fire in 2014) and elements of the Carnegie Library into a new plaza area on the river. A new parking structure similar in architectural design to one of the former mill buildings was also constructed. The city and Historic Columbus partnered to move and save four historic structures that would be impacted by the campus. This move became known as the 1998 Parade of Homes.

William H. Young, with the help of N.J. Bussey and young G. Gunby Jordan, reestablished what had been the Eagle mill. Quite appropriately, they added the name phoenix, the mythical Egyptian bird which rose from its own ashes. Young purchased land in modern day Phenix City, Alabama and created mill villages for his workers. Browneville, built 1862-1863 and named for an Eagle Manufacturing employee, was an example of one of the thriving mill villages owned by the textile giant. In 1879 the Columbus Daily Enquirer featured a history of Browneville, stating that it boasted good schools, lodges, churches, stores, and more. The company also offered savings accounts for their operatives. Prior to the construction of Browneville, housing for mill operatives consisted of at least five boarding houses in Columbus and 40 mill houses on the Alabama side of the river. Mill No. l (10,000 spindles and 135 looms) of the reorganized Eagle and Phenix Manufacturing Company began operating in 1868. During the 1870s the company expanded more rapidly than any other southern textile firm, adding Mill No. 2 (15,000 spindles and 350 looms) in 1871 and Mill No. 3 (20,000 spindles and 800 looms) in 1878. During the winter of 1880-1881, the company engineer, John Hill, installed Brush arc lights in Mill No. 3. By 1880, the Eagle and Phenix led the South in the value of its textile product ($1,500,000). Visitors to Columbus, especially during the 1881 Atlanta Exposition, marveled at the company's size and diversified products (144 different styles of cotton and woolen goods). Its growth leveled off in the 1880s and stagnated in the early 1890s.

The purpose of the mill village was to house workers. Some owners also began to provide schools, entertainment, and churches. Entertainment throughout the latter half of the 1800s included a yearly picnic hosted for mill workers where the Eagle and Phenix Brass Band played for the crowd. These picnics were a very big deal at the time. The tactics of offering housing, savings, schools, churches, etc. were seen by business leaders as a way to keep families committed to working for the mills, but also offered some stability for those families. However, the work hours were long, the job monotonous, noisy and dangerous and mill owners held tight control over the mill workers’ lives. In 1880, Eagle and Phenix employed 213 children, 555 men, and 917 women. In 1896, the mill went into receivership and was purchased by G. Gunby Jordan. One of Mr. Jordan’s investors was W. C. Bradley. G. Gunby Jordan owned the mill from 1896 to 1915 while W. C. Bradley served on the Board. In 1915, W. C. Bradley became president and owned the Eagle & Phenix Mill from then until 1947. From 1947 until 2003 several different companies including Reeves Brothers, Inc., Fieldcrest, and Pillowtex owned the mill property. All of the structures have been modified to some extent during their 150-year history. In December of 2003 the mill property was repurchased by W. C. Bradley Co. The W.C. Bradley Co. Real Estate Division is revitalizing the complex through the adaptive re-use of the site as condominiums, apartments, restaurants, and offices.

The power system of the antebellum industrial riverfront lots consisted of a dam (1844; at the present 14th Street bridge), a head race extending southward along the eastern side, and flumes that carried water across the tail race initially to water wheels and later to turbines. During the late 1850s, the Eagle Mill built (and then rebuilt in 1866 & 1869) a wooden rafter dam farther down the river. In the summer of 1882, the company engineer, John Hill, designed and supervised construction of the rubble masonry (8,100 cubic yards), gravity dam. Flumes continued to supply water to the rear of each mill building. In 1899-1900, the two existing wheelhouses were erected. In the lower powerhouse, two 45 inch and two 48-inch Holyoke Hercules turbines (mounted in twelve-foot flumes) drove two shafts which spanned the tail race and operated Mill No. 3. (The fifth or middle turbine (48 inch) was added later.) In the upper powerhouse, two shafts from four 54-inch Holyoke Hercules turbines (in open wheel pits) turned two rope drives along the eastern wall of the tail race. The interior one powered Mills No. l and 2. The outer one, rigged over a tower, served the dyehouse and the northern end of the plant. Its inefficiency led the company to shift to electric motors in those areas and install a 500 K1v., vertical generator over the No. l turbine (northwest). In 1914, a brick story was added to the upper powerhouse and three more generators (580 Kw.) were placed over the remaining turbines. In 1920-1921, similar conversions in the lower powerhouse resulted in the installation of five generators: two 500 Kw (NW, SE) and three 400 Kw. (Center, NE & SW). The powerhouses have also been adaptively re-used as the other structures within the Eagle and Phenix Mill Complex. The powerhouses now serve as event venues.

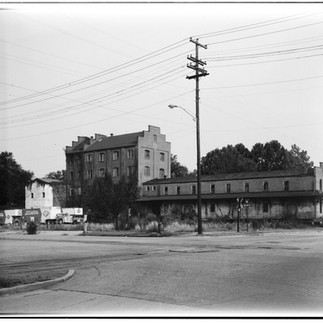

Rebuilt in the late 1860s, the warehouse buildings pictured above covered two blocks. They were expanded and modified for the next forty years. The modern Bradley Company began as a cotton-factoring business, Bussey-Goldsmith and Company, which W. C. Bradley and his brother-in-law Samuel A. Carter bought in the late 1880s. They changed the firm’s name to Carter and Bradley and expanded the firm’s business to include the manufacturing of fertilizer and the retailing of groceries. In 1895, Carter sold his portion of the company to Bradley, who changed its name to the W. C. Bradley Company. Over the next thirty years, Bradley further diversified his holdings by investing in banks, textile mills, steamboats, farms, Coca-Cola, and the Columbus Iron Works. The W.C. Bradley Company eventually became the owner of the entire two blocks. Today, the W.C. Bradley Co. is comprised of four companies focused on home and leisure products and services. These include the W.C. Bradley Real Estate, LLC, Zebco Brands, Char-Broil, and Lamplight. Over the past thirty years, the company has restored the many buildings that comprise this city block. It has included a variety of other businesses in addition to the W.C. Bradley Co. and the W.C. Bradley Co. Museum.

A. Clegg, an Englishman, migrated to Columbus during the antebellum period. On April 2, 1855, he settled in Columbus, where he was employed in the Eagle Mill and later, the Eagle & Phenix. In 1872, he went into the manufacturing of cotton goods on his own account, and in 1882 erected the Clegg Manufacturing Company building – a small, steam-powered factory. He was the president of the company with his son, John F. Clegg, as secretary and treasurer. Mr. Clegg was called one of the best mill men in the South in the 1887 publication The Industries of Columbus, Georgia. The company employed eighty hands and manufactured the celebrated Mitcheline bedspreads, cotton checks, ginghams, stripe and cottonades. It was located on the east side of the 1600 block of Second Avenue. This mill with its single product was typical of many southern companies launched during the 1870s and 1880s. Clegg died in 1894 or 1895 and the mill stopped operating by 1898. Burnham Van Lines (a national company with headquarters in Columbus) utilized the building as a warehouse for many years.

Established in 1854, Empire Mills, a steam-powered grist mill, was the city's largest from 1875 to 1890 under the proprietorship of George Waldo Woodruff. The company's proximity to the riverboat landing allowed it to supply flour, meal, and other products for the river trade to the agricultural areas south of the city. The grist mill closed in 1931, but the Empire Company continued to sell brick, ice, and coal there. The northern buildings of the complex (including the antebellum grist mill) were demolished by the early 1970s. During the summer of 1977, Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) planners studied the remaining structures (western section, ca. 1875; tower, ca. 1904; and eastern end, ca. 1885) and suggested possible adaptive uses. The mill is one of the earliest examples of adaptive re-use in Columbus. It was renovated and expanded in 1980 to become a convention hotel for the new Columbus Convention and Trade Center (historic Iron Works) across the street.

In the late 19th century, the Eagle and Phenix played a dominant role in the city’s economic life. When the 1873 depression struct, the company issued currency which was the only circulating medium in the area. A New York merchant advertised to exchange his dry goods for $100,000 worth of this Eagle and Phenix script. When telephones were installed in 1880, the Eagle and Phenix was assigned telephone numbers 1 and 2. Even the city’s political factions split according to those who supported the leadership at the Eagle and Phenix and those who opposed it. The leader of the anti-Eagle and Phenix faction, R.J. Moses, readily admitted, however, that without William H. Young Columbus would be a “dead town.”

Swift Manufacturing Company, Sixth Avenue (1883)

Next Week: We are moving into the late 19th century and turn of the 20th century to include Goldens Foundry, Swift Manufacturing Company, Paragon/Hamburger Mill/Bradley Manufacturing, the Columbus Railroad Company Powerhouse, and others. We will also highlight our community's bridges.

Don't forget...

Thanks to your continued support and investment, you have provided families with new roofs, scholarships for our community's children to continue their dream of college; and needed grants to save our historic resources. Approximately $605,000 was put to work in 2021 thanks to you! Thank you for all you do for preservation in Columbus.

Pictured (L to R): Walker Watkins, Debbie Lipscomb, Palmer Colson, and Justin Krieg.

Comments