Columbus, Georgia Downtown Churches: Trinity Episcopal Church (Part 4 of 6)

- Historic Columbus

- Sep 23, 2021

- 12 min read

For the month of September, we're highlighting more than just churches on our Instagram and Facebook! Please check us out on social media - @historiccolumbusga on Instagram and Historic Columbus on Facebook.

Sources: Columbus, Georgia in Vintage Postcards, Kenneth H. Thomas Jr., Historic Columbus Foundation Archive, and First Presbyterian Church of Columbus, Chattahoochee Valley Regional Library System Postcard Collection, A Power For Good: The History of Trinity Parish Columbus, Georgia, Lynn Willoughby.

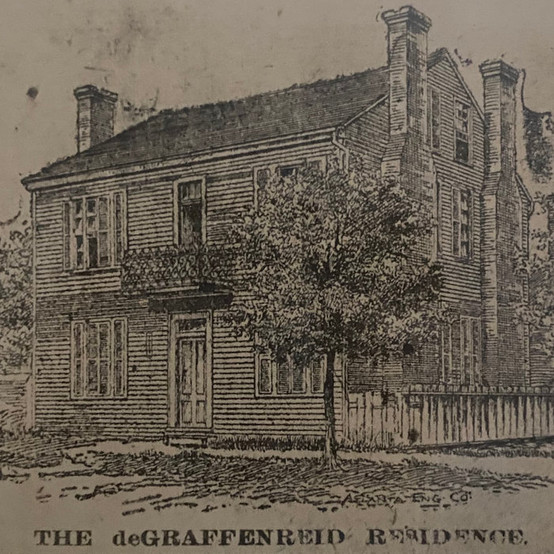

Governor John Forsyth had recently been elected Governor of Georgia when Columbus came into being in 1828. Commissioners Ignatius A. Few. Elias Beall, Philip H. Alston, James Hallam, and Edwin L. deGraffenreid were appointed by him to lay out the town, in accordance with an Act of the Legislature. There were already approximately 900 inhabitants living in what would become Columbus and it was the job of the Commissioners to plan out the new town. Dr. Edwin L. deGraffenreid was born in Lunenburg County, Virginia in 1798. He was a descendant of Baron Christopher deGraffenreid of Switzerland, who brought a group of people to the new world on account of religious persecution. Dr. deGraffenreid later moved to North Carolina, where he married Patsy Kirkland. They moved to the Coweta Reserve in 1825, where he became a leading citizen and established a large family. He was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, and a friend of Daniel Webster. The sprawling frontier settlement, with its very wide streets suggested by Dr. deGraffenreid as a health measure, was fast assuming the new look of a prosperous trading town.

His home was located on the southeast corner of First Avenue and 12th Street, what is now a parking lot adjacent to Trinity Episcopal Church and the 12th Street Post Office. The house was said to be the first brick building in the city, three years being required for its construction. He and his family occupied it in 1831, though it was not completed at the time. The home was on the eastern limits of civilization, all beyond being a dense woodland. On August 17, 1834, six years after the City of Columbus was established, a group met in the home of Dr. Edwin Louis de Graffenried. The founders of the parish had no rector, no bishop and no building; but they persevered, and in December 1834, The Georgia General Assembly enacted the articles of the Columbus Episcopal Church; and for the first time, the name “Trinity” appears in the historic record. Trinity was Georgia’s fifth Episcopal Church. The physician, as most of his family, was an Episcopalian. It was largely due to his efforts, that this denomination began in Columbus at such an early date. The parish was organized in 1834, and two years later the church was built across the street from the present location of Trinity Episcopal Church on 1st Avenue. No doubt it was Dr. deGraffenreid's influence that caused the church to be built close to his home.

Construction of the church was described as sporadic, with delays due to financial considerations as well as the threat of warfare near the frontier town of Columbus. The building was finally completed in 1837, and Trinity’s first “Divine Service” was held on June 4th of that year. From the time of its founding and until the completion of its first church building, services were held at the deGraffenried house, at the neighboring Presbyterian house of worship, and at the “Female Academy.” The location of the services was a problem, but not as much as was the lack of a permanent minister. Two church leaders quit, frustrated by the “unorganized state of the congregation,” according to Lynn Willoughby’s book, A Power For Good, The History of Trinity Parish; and it was not until 1837 that the Rev. William D. Cairns became Trinity’s first Rector and brought stability to the parish. Trinity Parish counted twenty people as communicants in 1836. Only eight persons communed at the first administration of the Eucharist in the new building on July 9, 1837. Even though five adults were baptized in the year following this Eucharist, four died and another left the parish, leaving the total number of communicants unchanged.

Old Trinity's interior, drawn by Garry Pound based on a stereoscopic photograph courtesy of Frank Schnell and The Columbus Museum.

A depression was also settling in across the country. America’s economic bubble of the 1830s, based on cheap Native American land and high cotton prices, burst in 1837. Cotton prices plummeted, creating a trade deficit in the South; this negative cash flow caused local banks to tighten credit, and most eventually failed. In an economy based solely on credit (cash transactions were all but forbidden by the banking conditions of the times), the lack of it caused financial ruin everywhere. The peril continued from 1837 until 1842, casting a long shadow over trinity’s new – and as yet unpaid for – building. Rev. Cairns was young and energetic, and seemed to have enough optimism for them all. Throughout his tenure at Trinity, he was always looking outwardly and thinking inclusively, preaching wherever two or more were gathered in His name. In addition to his pastoral duties, Cairns became principal of the Columbus Female Academy in 1839. Thanks to friends and Episcopalians in Macon, Savannah, Augusta, and Charleston, as well as the strenuous efforts of its own people, the majority of the debt to pay the builder, George Smith, for his construction of the church was paid by 1841. The membership of Trinity had also risen that same year to 47.

Outside of his clerical duties, Rev. Cairns also administered the Dillingham estate. Cairns’ wife was Lucy Elizabeth Ticknor Dillingham, widow of George Washington Dillingham, a prominent merchant who died in 1834. This facet of Rev. Cairns life brought him sustenance but also ambivalence. As a planter, the priest from New York found himself in the uncomfortable position of owning slaves, including the two Bailey brothers. When Cairns fell into owning them, the boys were approximately ten years old. So, Cairns educated them (an act that was illegal throughout most of the South) and gave them religious instruction. Then, at his death in 1850, the rector freed Edmund Bailey and his brother.

Edmund grew to be a store owner and a preacher. Because of his superior education, he was naturally set apart as a Black community leader. His youth, spent under the guidance of a devout priest, prepared him to be a religious leader as well. Bailey became pastor of St. John’s African American Episcopal Church (pictured above and located on 5th Avenue) in Columbus and was responsible for building the chapel of the church. Bishop Stephen Elliot also wrestled with the conflicting themes of slavery and Christian ministry. He encouraged that all slaves be taught religious instruction and that they should be made to feel that they are welcome at the church. The rector of Trinity parish took this to heart. In 1841, Rev. Cairns baptized nine African American adults and six infants, confirmed one parishioner, conducted nine African American weddings, and added twenty African American children to the Sunday School rolls. When white and Black were added together, the parish membership blossomed to 72, with 100 children enrolled in Sunday School. Numbers of African American members would decline by 1850 down to four due to churchmen Edward B. Fishburne and Thomas M. Nelson developing new plantations near Albany and moving many of their enslaved laborers to the new locations. In addition, several baptized slaves were also organized into a separate church called St. Cyprian’s within the same parish.

The Civil War had ended, and the people of Trinity, like people throughout the nation, set their minds to the task of rebuilding their lives and businesses. The burned-out Eagle Mill rose like a phoenix from the charred ruins to become the Eagle & Phenix. It and other newly renovated Columbus factories symbolized the dawning of the industrial age. After the passing of Bishop Elliot and the Rev. William Hawks, Trinity Church entered a time of instability. During the five years between 1865 and 1871, the church was without a rector three times.

Trinity Parish achieved its former vitality under the care of Rev. Harris. In only one year’s time, the Sunday School enrollment tripled its membership to serve 150 white and 30 Black students. The rector also organized a Parish Society which undertook missionary and benevolent work connected with Sunday School. The rector’s most ambitious project was the creation of a new parish school, which opened in October 1871. The new age of industrialism permitted some to experience a luxury they had only dreamed of before – free time. More and more, people found time for a game of baseball or an excursion down the river, taken just for enjoyment. The Trinity women decided to capitalize on this new demand for entertainment by holding a musical concert and selling tickets. The first affair was successful enough that the ladies were emboldened to plan an even bigger event.

Two blocks away from the church, Francis J. Springer was putting the finishing touches on his opera house. Some citizens thought that “amusements” were “demoralizing and corrupting,” but these sentiments were not shared by the six or seven hundred people who attended the second musical program by the people of Trinity Church and the first-ever performance held at the new Springer Opera House. The Springer’s opening-night performance of February 21, 1871 was billed as a “Grand Amateur Concert by the Ladies and Gentlemen of Trinity Church assisted by Prof. Chase and other Amateurs.” The affair was pronounced a great success.

For the time being, the church abandoned the idea of a larger place of worship. They decided instead to use the money earned by the benefit concerts toward the purchase for a rectory in 1872, borrowing the additional five thousand dollars needed for payment. This first rectory was located across First Avenue from the sanctuary, on the site of the modern-day church. In 1886, the Town Commons Commission donated four city lots to Trinity. With money coming in steadily and the church’s net worth increasing through real estate holdings, the vestry dared to dream again of a new church building. While they did not intend to build on the commons lots, they could sell them, along with the old church structure, to pay partially for the new building. After another couple of years, the vestry felt they could shoulder the financial burden of a new building. The cornerstone of the present Trinity Episcopal Church was laid in 1890, and Trinity moved into its new building on August 2, 1891. The formal dedication of the church had to await the consecration of a new bishop, so the long-awaited consecration service did not occur until May 22, 1892. It is of interest that only three symbols from the original church have survived the ages and are in the present church: The Hyslop bell, a 900-pound bell given by New York merchant Robert Hyslop in 1837; marble memorial tablets honoring Rectors Cairns and Hawks; and the altar cross, dating to 1879.

This church is located just north of the First Presbyterian Church at 1130 First Avenue.

The Congregation was founded in 1834 and this building opened in 1891.

The church is still active and looks much the same, although there were later additions.

An identical card was sent as a Christmas card by the rector in 1905.

(Columbus, Georgia in Vintage Postcards, Kenneth H. Thomas Jr.)

The era between the turn of the century and World War I brimmed with technological advancements. The new scientific developments were reflected in the installation of a telephone in the vestry room and in the rectory in 1903. The vestry investigated buying an electric motor to run a blower for the organ in 1907, but postponed this purchase. For the time being, a young boy pumped the blower manually each Sunday. In 1909, the church was rewired, and the lighting changed from carbon to tungsten lamps. Religion was a major component of Progressivism, and Episcopalians stood in the vanguard of the national reform movement. Proponents of the social gospel believed the church had a social responsibility to alleviate poverty, ignorance, labor exploitation, war, and suffering of all kinds. This applied Christianity linked reform with religion and infused Progressivism with “a powerful moral drive” – and its most dynamic element was female.

There were also two missions established during this same time period. On October 25, 1891, two months after Trinity moved into its new church building, another cornerstone was laid for a new Episcopal chapel named St. Mary the Virgin (pictured below on the left) – located on the southeast corner of 3rd Avenue and 17th Street on the edge of High Uptown. It would serve Rose Hill, North Highlands, and some of Wynnton. The second mission was founded in 1908 for African Americans – St. Christopher’s Mission (pictured below on the right) – on the northeast corner of 5th Avenue and 9th Street. Both buildings have since been demolished.

In 1926, Trinity expanded its church. The new building comprised of Sunday School and other meeting rooms, a chapel, and a parish hall. The chapel was the epitome of simplicity – bare white walls, exposed beams, and unadorned windows. Not until later was an organ added, as well as stained-glass windows and two religious paintings.

Postcard of Trinity Episcopal Church and Parish House, Columbus, GA–1900/1950 (Chattahoochee Valley Regional Library System Collection)

During World War II, Trinity supported the troops at Fort Benning with Sunday night socials and suppers. Also, about one-third of the choir was made up of a constantly changing group of military personnel. Most of them came to the Sunday night service and fellowship hour, then joined the choir. While the soldiers were overseas, the people back home wrote letters, practiced air raid drills, and prayed a lot. Looking beyond the walls of Trinity, the rector encouraged the founding of a senior Boy Scout unit for Star, Life, and Eagle Scouts; a new Boy Scout Troop; and a Brownie Scout troop. All of these were organized in 1947. The dream of a parish school became possible at this time with the donation of a home and three-and-a-half acres located at 2112 Wynnton Road. The neophyte institution named Trinity School began by offering two years of kindergarten and the first four grades, with the intention of adding a grade each year until a full grade school was achieved. Over time this educational experiment proved highly successful, and although the character of the school changed as it grew, the institution itself survived and flourished, evolving into Brookstone School, an independent college preparatory school no longer affiliated with Trinity Church. Another change in postwar America was seen in the demographics of city and church. By the end of 1956, Trinity’s total communicants had grown to over one thousand. Automobile use had become universal, and the pattern of urban development resulted in Americans sprawling out into new suburbs. These trends encouraged the establishment of new churches and missions, and Columbus was no exception. In 1957, the rector, wardens, and vestry of Trinity unanimously petitioned the Diocese of Atlanta for the expansion of the Episcopal Church in Muscogee County. By 1958, St. Thomas Mission on Hilton Avenue was established.

Change seemed to be the order of the day by the late 1960s and 1970s at Trinity Church, as it was for the nation. The Civil Rights Movement, a more active younger generation wanting to sing folk music during church services, adoption of a new prayer book, and the ordination of women being approved by a narrow margin at the General Convention in 1976 were all threatening to divide the church in their own ways. Several families left Trinity at this time. A few began attending other downtown churches. Another group eventually formed a church association with the Anglican Catholic Church. This group built a new church on Broadway in 1986 and called it St. George. After the contention caused by the changing liturgy, the ordinance of women into the priesthood, as well as other stances defined as more liberal by some, the Episcopal Church was more resilient than it ever had been. Those who remained had made that decision after powerful introspection – something good for everyone’s faith. Although changes still lay ahead for the national church and for Trinity, the two had weathered the storm relatively intact and appreciated the sunshine more than ever.

The early 1980s also presented what could be called a turning point for the parish. While the parish was still in pain from its recent divisions, outside of its walls the people of Columbus were also suffering. This was the moment when the need became clear to place a larger emphasis on outreach and caring for others. In addition to its commitment to the House of Mercy, Trinity’s new mission work also included support of the Alliance for Battered Women, Alliance for Children, Younglife, Stewart Community Home, Appleton Family Ministries, and Troop Six of the Boy Scouts. During the 150th anniversary year (1984) the vestry focused not only on it outreach projects but also on its church facilities. They purchased the parking lot immediately north of the sanctuary (the site of Dr. deGraffenried’s home) and embarked on a capital funds drive to complete needed renovation and construction projects. The number of congregants, especially young families worshipping at Trinity increased in the 1990s, with the addition of some new services and the expansion of other congregational activities. Today, you can also include Valley Interfaith Promise as one of the church's outreach programs. While new traditions were started, some of the older ones were modified or even discontinued. However, many rituals of worship with deep meaning for Trinity’s members have remained unchanged, and Trinity's commitment to the Columbus community has not waivered. Rev. Timothy Graham, a Georgia native, has served as rector to the congregation since 2012.

Over its 165 years, the parish has survived eras of war and of peace, boom times and bust, times of exploding activity, and seasons of slumber. Inside its sanctuary, the changing faces of parishioners have watched young rectors growing older and wiser; they have listened to the high, wavering voices of a boys' choir mature into baritones and basses. They have intoned the same prayers their parents and grandparents said, christened their babies, and said farewell to their departed. From its pulpit, the careers of three bishops were launched, and speakers, as varied as the Archbishop of Canterbury, philanthropist George Foster Peabody, and sportscaster Red Barber, have appealed to their better natures. Each generation has been a caretaker of this sacred place, honoring and augmenting the physical presence of Christ's church on this earth. Less tangible, but no less significant, has been the parishioners' acts of Christian love that have touched many more lives than ever have been members of Trinity Parish.

Next Week: Holy Family! If you aren't already a member, we hope you will join us! I also want to encourage you to follow Historic Columbus on Facebook and Instagram for more posts on our community's history. Thank you all for your continued support of Historic Columbus! Elizabeth B. Walden Executive Director

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.