SOURCE: Robert Winship Woodruff: A Biography of the Boss by Charles Elliott, 1979. Heritage Park: A Celebration of the Industrial Heritage of Columbus, Georgia by Dr. John S. Lupold, 1999.

Coca-Cola was an infant of some three years when Robert W. Woodruff was born. As a nation, we were little more than a century old. We were near the end of Reconstruction, and the horse and buggy era was at its height. Coca-Cola didn’t burst upon the scene in a shower of stars. Its birth was an obscure event, unheralded by headlines. John S. Pemberton first arrived in Columbus in the early 1850s. In Macon, he had studied Thomasonian medicine, a system that used botanical cures, and in Rome, had briefly practiced medicine before he moved to the banks of the Chattahoochee. In Columbus in 1855, he opened a retail and wholesale drug business specializing in materia medica. By 1860, he was also operating a drug store with Robert Carter. Pemberton entered the Civil War as a first lieutenant in the Confederate calvary and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel before being wounded during the Battle of Columbus. Six months after the end of the war, Pemberton opened two companies: Eagle Drug and Chemical House, a retail establishment, and John S. Pemberton & Company, Wholesale Drugs. Pemberton employed chemists and pharmacists who distilled a whole range of pharmaceuticals, patent medicines, hair restorers, perfumes (such as “Sweet Southern Bouquet”), paints, photographic chemicals, and a great variety of sparkling soda waters he dispensed from an “elegant marble fount” in his drugstore. One of these drinks was French Wine of Coca, which some historians believe was the same formula as Coca-Cola. Whatever the contents of that drink, it was not called “Coca-Cola” in Columbus. Apparently, Pemberton was disappointed with the commercial possibilities of Columbus. It lacked the railroad network and the access to wider markets available in Atlanta. So, he moved his family to Atlanta by 1869.

Even if Pemberton had never developed Coca-Cola, he would have had a significant career as a pharmacist. He relocated to Atlanta to supervise the firm of Pemberton, Wilson, Taylor and Company, which had been organized in 1869 and produced similar products as his Columbus facility. It also included an analytical laboratory that provided the first analysis of the contents of agricultural chemicals, a constant concern for farmers. During this period, Pemberton also organized a chemical firm in Philadelphia and established at least eighteen business in Atlanta between 1870 and 1888. He also served as a trustee for the Atlanta Medical College and on the first state examining board that licensed pharmacists. He was a professional chemist and an entrepreneur. He never mixed ingredients in a black kettle in his backyard as some biographies have claimed. Pemberton began selling Coca-Cola in 1886, the year prohibition started locally in Atlanta. The name French Wine of Coca was then changed to avoid any reference to alcohol. Created especially for soda fountains, it could be put on the market by the drink at five cents a glass. His bookkeeper, Frank M. Robinson, named it Coca-Cola and in Robinson’s flowing script created the “logo.” Neither has changed to this day.

One of the pharmacies in Atlanta that he had done a large part of his business was Jacobs' Drug Store, located on Norcross Corner, which later became known as “Five Points.” Pemberton walked the short distance between his office and laboratory at 107 Marietta Street to tell Joe Jacobs and Willis Venable about his new product. The next year, Pemberton was granted a registration by the U.S. Patent Office as “sole proprietor” for “Coca-Cola syrup and extract.” This was the first trade-marked beverage in the soda fountain field. Pemberton then organized capital to market his drink, as was his usual practice. Several druggists and some investors joined him. The petition for incorporation was filed in March of 1888. Pemberton sold two-thirds interest in Coca-Cola to his friend George S. Lowndes and Willis Venable (a clerk in Jacobs’ Drug Store) for $1,200 (plus $283.29 for his equipment and supplies). He retained one-third interest at this point. When Lowndes and Venable failed to get Coca-Cola off the ground, they soon sold their two-thirds interest to Woolfork Walker and his sister, Mrs. M.C. Dozier.

On April 14, 1888, four months before Dr. Pemberton died, he and his son Charles signed a document releasing all claims in Coca-Cola to Walker, Candler and Company – a partnership that included Woolfork Walker, Asa G. Candler, and Joe Jacobs (owner of Jacobs’ Drug Store). For this release, Pemberton and his son were paid the sum of $550. It was said that Asa Candler came to Atlanta from Cartersville in 1873 with a dollar and seventy-five cents in his pocket. He went to work for George Jefferson Howard and five years later married Lucy Elizabeth Howard, much against her father’s wishes. In another five years, Candler and his father-in-law became reconciled and opened the retail drug firm of Howard and Candler. In 1886, Asa Candler bought out Howard’s interest and changed the firm’s name to Asa G. Candler and Company. Frank Robinson, who had left Pemberton when its originator sold two-thirds interest in his rights, had gone to work for Candler, who had put him to work manufacturing the syrup. In August of 1888, Asa Candler paid $1,000 to Walker and Mrs. Dozier for their interest in the drink and became sole owner of Coca-Cola. He was involved in the promotion of a number of patent medicines in which he was at first more interested, but with increased sales, his interest in Coca-Cola developed and he began to advertise the new drink. To the words “Delicious” and “Refreshing” he added “Exhilarating” and “Invigorating.” For $2,300, Asa Candler had purchased a product that less than two decades later, his children sold for $25 Million.

In 1892, Candler moved the Coca-Cola manufacturing operation from his drug store on Peachtree Street to a new address at 42 ½ Decatur Street, incorporated it as The Coca-Cola Company and launched an extensive program of sales and advertising that expanded his drink from a local to a nationwide product by 1895. It is generally considered that the Coca-Cola bottle originated in 1899 with Benjamin F. Thomas and Joseph Brown Whitehead, two young Chattanooga lawyers. But the practice of putting “ready-to-drink” Coca-Cola in bottles for home consumption was started five years before that in 1894 by Joseph A. Biedenharn, who managed Biedenharn Candy Company, a confectionery and wholesale grocery firm in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

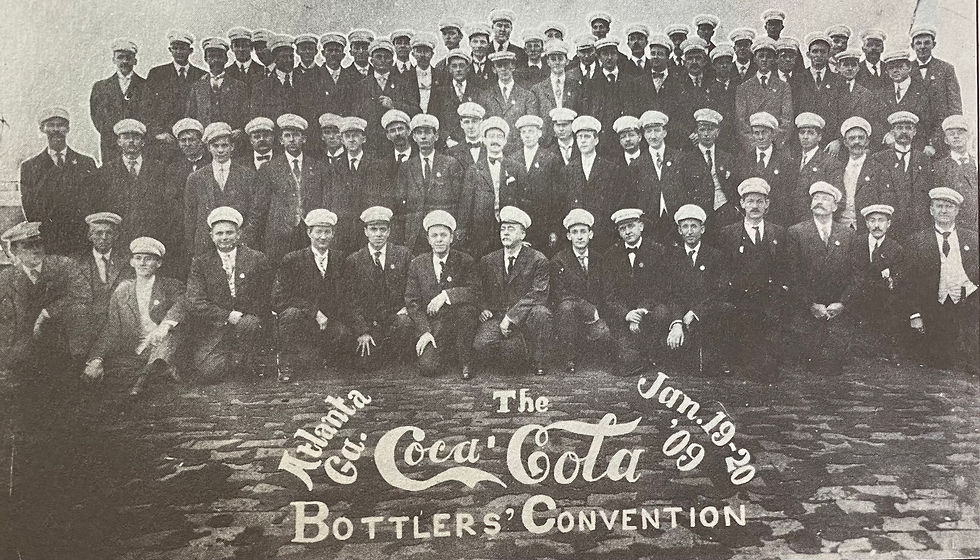

Local bottlers shared in the Coca-Cola bonanza. These included Columbus Roberts (pictured below), one of ten children born to a Lee County, Alabama family in 1870. At age 18, he moved to Atlanta, but left four years later to become a wholesale grocer in Opelika. Then in 1893, he began bottling soda waters and making some money. But his big break came in late 1901 when he signed a contract giving him exclusive rights to bottle and distribute Coca-Cola in Opelika and Columbus, in return for agreeing not to bottle any other drink. In 1902, he moved to Columbus and created the first Coca-Cola bottling plant in the city. His son, Columbus Roberts, Jr., carried on the bottling business. Before the new year of 1902, a total of seven bottling plants were in existence in the United States. By 1909, there were 377.

As with any new enterprise, the company went through its own special growing pains. It was natural that a product so popular should be imitated. There was no way to identify it when it lay with other bottles of carbonated drinks of the same color in a tub of ice, some of which were often sold as Coca-Cola. Even though bottlers affixed paper labels to their drinks, these softened and came off in the ice water tub. The story is that one unscrupulous bottler of other soda drinks purchased Coca-Cola syrup at soda fountains and made his own Coca-Cola of inferior quality, without benefit of contract. Others were marketing a similar product from syrup not supplied by The Coca-Cola Company. In 1916, there were said to be no less than 153 imitations of Coca-Cola. Against one of these – J.G. Butler and Sons – the company entered suit to protect its patents and distribution plan and received a court decision upholding its rights and system.

This was the same year that the distinctive Coca-Cola bottle appeared. Its objective was to get away from the other round drink bottles, all so much alike. Alex Samuelson, who worked for the Root Glass Company in Terre Haute, Indiana, had been trained as a glass blower in Germany. He conceived of the idea of a bottle built somewhat like a coca bean. This he perfected, but the bulge was so large that the bottle could not be properly handled by the equipment in the bottling plants. So, he trimmed it down and it was patented in his name. The new bottle was adopted by a committee of bottlers six to one and became an instant success with both the plant managers and the public. It has been in use since that date and is a recognized shape throughout the world. The bottle itself is a registered trademark, one of only a half dozen containers to be accorded this distinction.

In 1916 and the years following, other things were happening which were to affect the future of The Coca-Cola Company. That year, Asa Candler stepped down from managing The Coca-Cola Company, so that he could devote himself to real estate and politics. He remained a director in his company and put his son Howard as president. In 1917, Candler was elected mayor of the city of Atlanta. At Christmas that year, he equally divided all but seven shares of his stock between his wife and five children. They immediately began looking for a buyer and the next year the company was put up for sale. In September 1919, almost a year after the end of World War I, the Candlers were able to dispose of their stock. They buyer was a syndicate headed by Ernest Woodruff (pictured above), Robert’s father, and his old schoolmate, W. C. Bradley (pictured below). The syndicate was the Trust Company bank, along with two New York banks (Guaranty Trust Company and Chase Securities Company) that actually bought Coca-Cola. Candler did not realize who was behind the deal.

The sale was said to be the largest financial transaction that had ever taken place in the South, and Asa Candler, who owned only seven shares was not consulted. The sale price, $15 million in cash and $10 million in preferred stock, was more than ten thousand times the amount of money Candler had spent to purchase the entire Coca-Cola operation some 30 years before. The news of the sale so upset Asa Candler that he would not attend the board of directors meeting at which the sale was approved. The new company almost immediately issued five hundred thousand shares of Coca-Cola common stock at $40 a share. As its commission, the Trust Company of Georgia, which handled this transaction, was allowed to purchase stock at $5 a share, and the 88,000 shares it acquired in this manner would in 30 years be worth $90 million. However, the company would soon see struggles under the leadership of Samuel Candler Dobbs, nephew to Asa Candler, as president of Coca-Cola. With long-range mistakes, the general apathy throughout the company and an alarming decrease in the sale of syrup, the directors were fully aware new blood was needed. Two months later, Robert W. Woodruff was offered the job. NEXT WEEK: The early years of Coca-Cola under Woodruff's leadership.

Comments